Haymarket Affair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

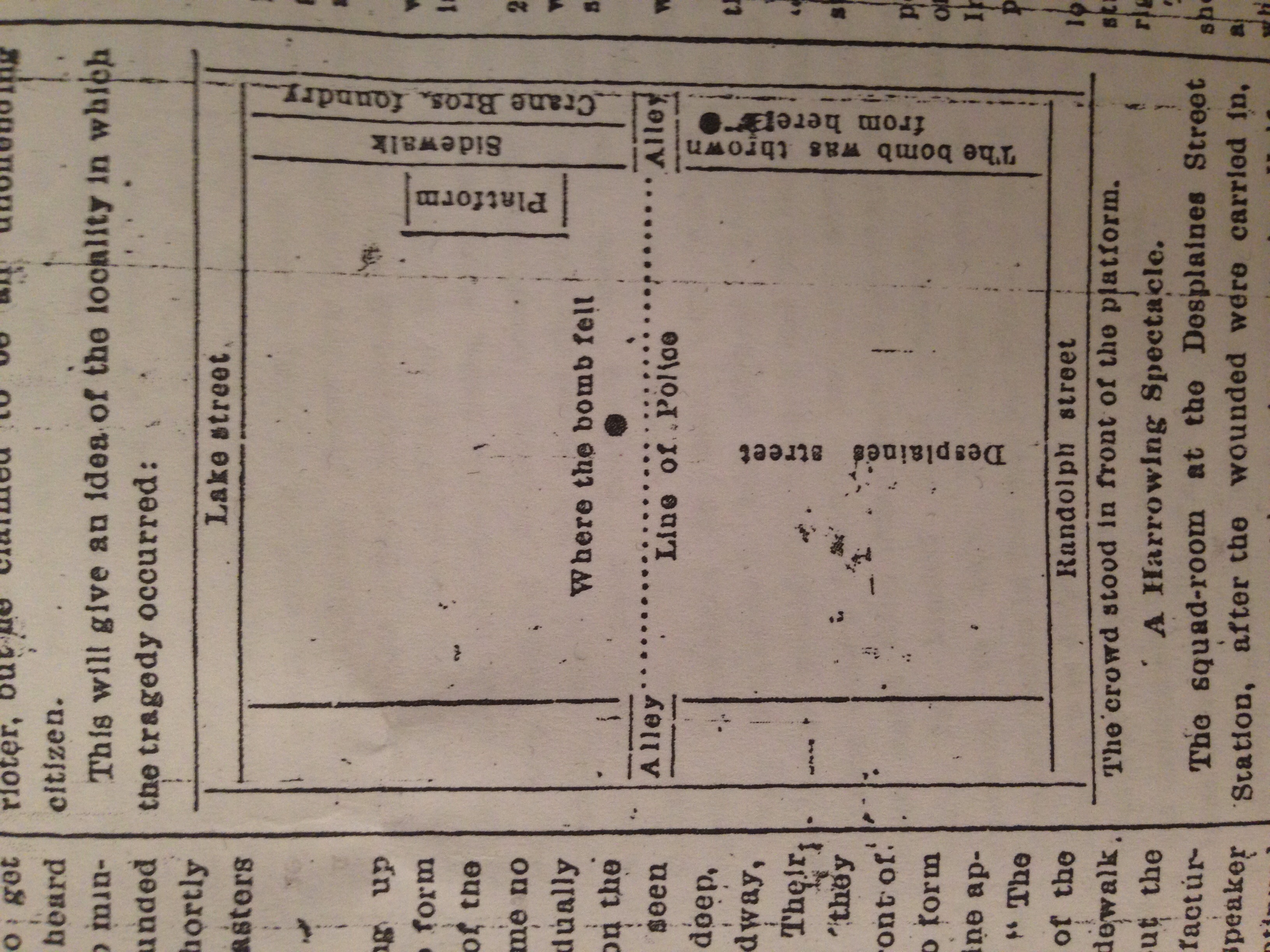

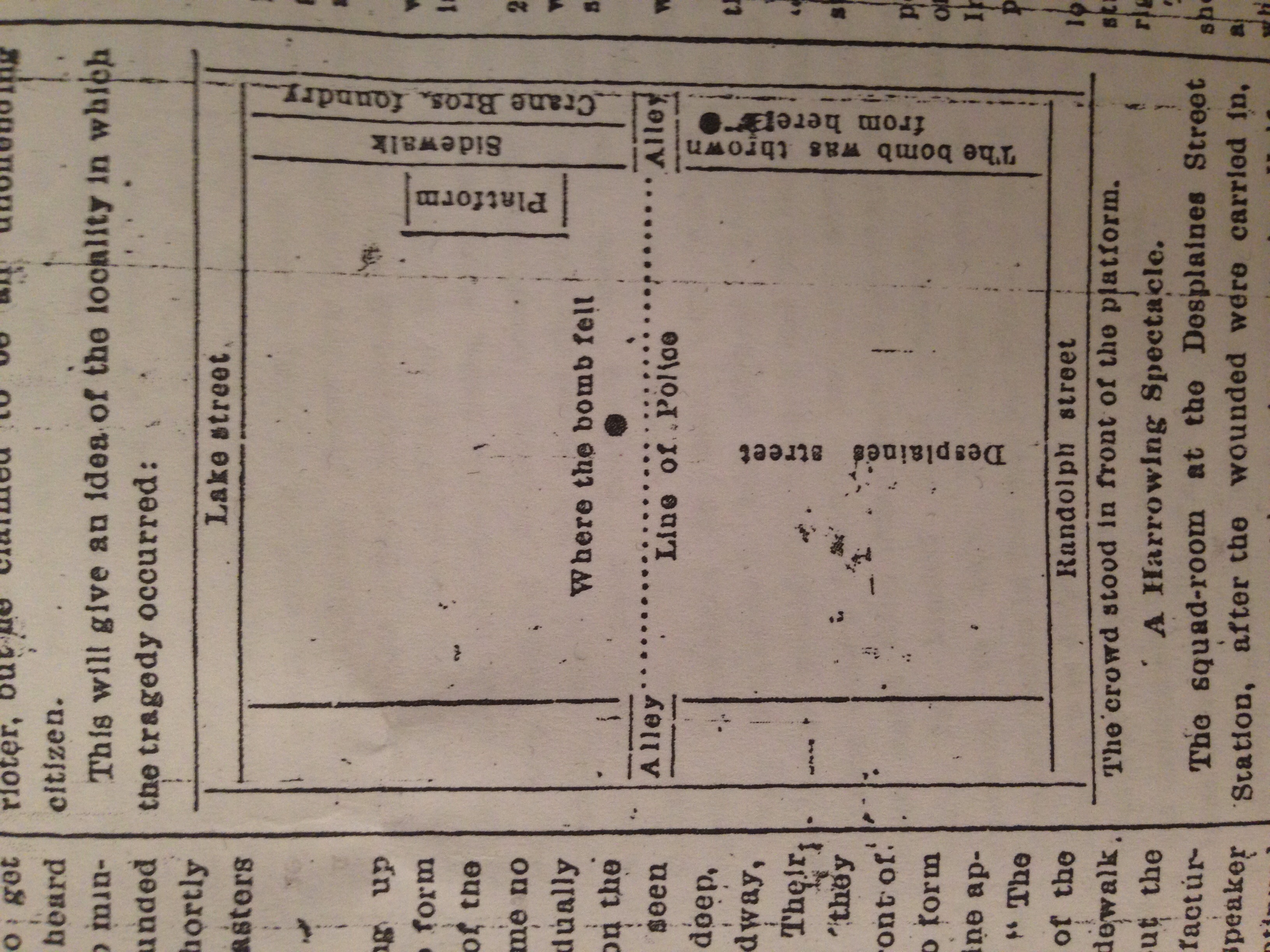

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at

The rally began peacefully under a light rain on the evening of May 4. August Spies,

The rally began peacefully under a light rain on the evening of May 4. August Spies,

At about 10:30 pm, just as Fielden was finishing his speech, police arrived en masse, marching in formation towards the speakers' wagon, and ordered the rally to disperse. Fielden insisted that the meeting was peaceful. Police Inspector John Bonfield proclaimed:

At about 10:30 pm, just as Fielden was finishing his speech, police arrived en masse, marching in formation towards the speakers' wagon, and ordered the rally to disperse. Fielden insisted that the meeting was peaceful. Police Inspector John Bonfield proclaimed:

A harsh anti-union clampdown followed the Haymarket incident and the Great Upheaval subsided. Employers regained control of their workers and traditional workdays were restored to ten or more hours a day. There was a massive outpouring of community and business support for the police and many thousands of dollars were donated to funds for their medical care and to assist their efforts. The entire labor and immigrant community, particularly Germans and Bohemians, came under suspicion. Police raids were carried out on homes and offices of suspected anarchists. Dozens of suspects, many only remotely related to the Haymarket Affair, were arrested. Casting legal requirements such as search warrants aside, Chicago police squads subjected the labor activists of Chicago to an eight-week shakedown, ransacking their meeting halls and places of business. The emphasis was on the speakers at the Haymarket rally and the newspaper ''Arbeiter-Zeitung''. A small group of anarchists were discovered to have been engaged in making bombs on the same day as the incident, including round ones like the one used in Haymarket Square.Avrich (1984), pp. 221–32.

Newspaper reports declared that anarchist agitators were to blame for the "riot", a view adopted by an alarmed public. As time passed, press reports and illustrations of the incident became more elaborate. Coverage was national, then international. Among property owners, the press, and other elements of society, a consensus developed that suppression of anarchist agitation was necessary while for their part, union organizations such as The Knights of Labor and craft unions were quick to disassociate themselves from the anarchist movement and to repudiate violent tactics as self-defeating.David, ''The History of the Haymarket Affair'' (1936), pages 178–189 Many workers, on the other hand, believed that men of the

A harsh anti-union clampdown followed the Haymarket incident and the Great Upheaval subsided. Employers regained control of their workers and traditional workdays were restored to ten or more hours a day. There was a massive outpouring of community and business support for the police and many thousands of dollars were donated to funds for their medical care and to assist their efforts. The entire labor and immigrant community, particularly Germans and Bohemians, came under suspicion. Police raids were carried out on homes and offices of suspected anarchists. Dozens of suspects, many only remotely related to the Haymarket Affair, were arrested. Casting legal requirements such as search warrants aside, Chicago police squads subjected the labor activists of Chicago to an eight-week shakedown, ransacking their meeting halls and places of business. The emphasis was on the speakers at the Haymarket rally and the newspaper ''Arbeiter-Zeitung''. A small group of anarchists were discovered to have been engaged in making bombs on the same day as the incident, including round ones like the one used in Haymarket Square.Avrich (1984), pp. 221–32.

Newspaper reports declared that anarchist agitators were to blame for the "riot", a view adopted by an alarmed public. As time passed, press reports and illustrations of the incident became more elaborate. Coverage was national, then international. Among property owners, the press, and other elements of society, a consensus developed that suppression of anarchist agitation was necessary while for their part, union organizations such as The Knights of Labor and craft unions were quick to disassociate themselves from the anarchist movement and to repudiate violent tactics as self-defeating.David, ''The History of the Haymarket Affair'' (1936), pages 178–189 Many workers, on the other hand, believed that men of the

The police assumed that an anarchist had thrown the bomb as part of a planned conspiracy; their problem was how to prove it. On the morning of May 5, they raided the offices of the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'', arresting its editor August Spies, and his brother (who was not charged). Also arrested were editorial assistant Michael Schwab and Adolph Fischer, a typesetter. A search of the premises resulted in the discovery of the "Revenge Poster" and other evidence considered incriminating by the prosecution.Schaack

The police assumed that an anarchist had thrown the bomb as part of a planned conspiracy; their problem was how to prove it. On the morning of May 5, they raided the offices of the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'', arresting its editor August Spies, and his brother (who was not charged). Also arrested were editorial assistant Michael Schwab and Adolph Fischer, a typesetter. A search of the premises resulted in the discovery of the "Revenge Poster" and other evidence considered incriminating by the prosecution.Schaack

"Core of the Conspiracy"

''Anarchy and Anarchists'', pp. 156–182. On May 7, police searched the premises of

"My Connection with the Anarchist Cases"

''Anarchy and Anarchists'', pp, 183–205. Lingg's landlord William Seliger was also arrested but cooperated with police and identified Lingg as a bomb maker and was not charged.Messer-Kruse, Timothy (2011), page 21 An associate of Spies, Balthazar Rau, suspected as the bomber, was traced to Omaha and brought back to Chicago. After interrogation, Rau offered to cooperate with police. He alleged that the defendants had experimented with dynamite bombs and accused them of having published what he said was a code word, "Ruhe" ("peace"), in the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'' as a call to arms at Haymarket Square.

The trial, ''Illinois vs. August Spies et al.'', began on June 21, 1886, and went on until August 11. The trial was conducted in an atmosphere of extreme prejudice by both public and media toward the defendants.Avrich, ''The Haymarket Tragedy'' (1984), pp. 260–262 It was presided over by Judge

The trial, ''Illinois vs. August Spies et al.'', began on June 21, 1886, and went on until August 11. The trial was conducted in an atmosphere of extreme prejudice by both public and media toward the defendants.Avrich, ''The Haymarket Tragedy'' (1984), pp. 260–262 It was presided over by Judge

The next day (November 11, 1887) four defendants—Engel, Fischer, Parsons, and Spies—were taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods. They sang the ''

The next day (November 11, 1887) four defendants—Engel, Fischer, Parsons, and Spies—were taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods. They sang the ''

"What Happened at Haymarket? A historian challenges a labor-history fable"

''National Review'', February 11, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

Among supporters of the labor movement in the United States and abroad and others, the trial was widely believed to have been unfair, and even a serious

Among supporters of the labor movement in the United States and abroad and others, the trial was widely believed to have been unfair, and even a serious

In 1889, AFL president

In 1889, AFL president

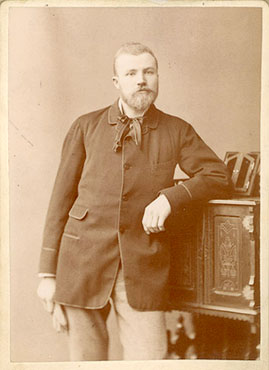

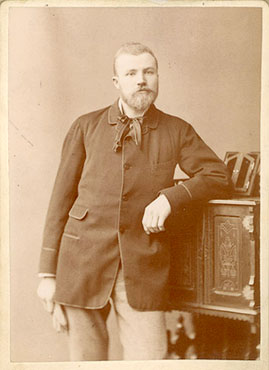

* Rudolph Schnaubelt (1863–1901) was an activist and the brother-in law of Michael Schwab. He was at the Haymarket when the bomb exploded. General Superintendent of the Chicago Police Department Frederick Ebersold issued a handwritten bulletin for his arrest for murder and inciting a riot on June 14, 1886. Schnaubelt was indicted with the other defendants but fled the city and later the country before he could be brought to trial. He was the detectives' lead suspect, and state witness Gilmer testified he saw Schnaubelt throw the bomb, identifying him from a photograph in court. Schnaubelt later sent two letters from London disclaiming all responsibility, writing, "If I had really thrown this bomb, surely I would have nothing to be ashamed of, but in truth I never once thought of it." He is the most generally accepted and widely known suspect and figured as the bomb thrower in ''The Bomb'',

* Rudolph Schnaubelt (1863–1901) was an activist and the brother-in law of Michael Schwab. He was at the Haymarket when the bomb exploded. General Superintendent of the Chicago Police Department Frederick Ebersold issued a handwritten bulletin for his arrest for murder and inciting a riot on June 14, 1886. Schnaubelt was indicted with the other defendants but fled the city and later the country before he could be brought to trial. He was the detectives' lead suspect, and state witness Gilmer testified he saw Schnaubelt throw the bomb, identifying him from a photograph in court. Schnaubelt later sent two letters from London disclaiming all responsibility, writing, "If I had really thrown this bomb, surely I would have nothing to be ashamed of, but in truth I never once thought of it." He is the most generally accepted and widely known suspect and figured as the bomb thrower in ''The Bomb'',

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons were buried at the

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons were buried at the

In 1889, a commemorative nine-foot (2.7 meter) bronze statue of a Chicago policeman by sculptor

In 1889, a commemorative nine-foot (2.7 meter) bronze statue of a Chicago policeman by sculptor  The Haymarket statue was vandalized with black paint on May 4, 1968, the 82nd anniversary of the Haymarket Affair, following a confrontation between police and demonstrators at a protest against the

The Haymarket statue was vandalized with black paint on May 4, 1968, the 82nd anniversary of the Haymarket Affair, following a confrontation between police and demonstrators at a protest against the  On September 14, 2004, Daley and union leaders—including the president of Chicago's police union—unveiled a monument by Chicago artist Mary Brogger, a fifteen-foot (4.5 m) speakers' wagon sculpture echoing the wagon on which the labor leaders stood in Haymarket Square to champion the eight-hour day. The bronze sculpture, intended to be the centerpiece of a proposed "Labor Park", is meant to symbolize both the rally at Haymarket and

On September 14, 2004, Daley and union leaders—including the president of Chicago's police union—unveiled a monument by Chicago artist Mary Brogger, a fifteen-foot (4.5 m) speakers' wagon sculpture echoing the wagon on which the labor leaders stood in Haymarket Square to champion the eight-hour day. The bronze sculpture, intended to be the centerpiece of a proposed "Labor Park", is meant to symbolize both the rally at Haymarket and

Haymarket Affair Digital Collection

Table of Contents

Haymarket Affair Digital Collection

The Dramas of Haymarket

Chicago Historical Society

1886: The Haymarket Martyrs and Mayday

Libcom

Haymarket Affair texts

at the Kate Sharpley Library

Illinois Labor History Society

Haymarket Martyrs' Monument

Graveyards of Chicago

The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists

Haymarket Trial

Famous Trials,

Chicago Anarchists on Trial: Evidence from the Haymarket Affair 1886–1887

The Haymarket Bomb in Historical Context

The Haymarket frame-up and the origins of May Day

Haymarket and May Day

{{DEFAULTSORT:Haymarket Affair Anarchism in the United States Anti-communism in the United States Communism in the United States Riots and civil disorder in Chicago Crimes in Chicago History of anarchism History of labor relations in the United States History of socialism History of social movements Labor disputes in the United States Political riots in the United States Protest-related deaths 1886 in Illinois 1886 labor disputes and strikes 1886 riots 1880s in Chicago Labor-related riots in the United States Terrorist incidents in the United States Labor disputes in Illinois May 1886 events 1886 crimes in the United States

Haymarket Square Haymarket Square may refer to:

* Haymarket Square (Boston), in Boston

* Haymarket Square (Chicago), in Chicago

* Haymarket affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, United States. It began as a peaceful rally in support of workers striking for an eight-hour work day, the day after the events at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, during which one person was killed and many workers injured. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at the police as they acted to disperse the meeting, and the bomb blast and ensuing gunfire resulted in the deaths of seven police officers and at least four civilians; dozens of others were wounded.

In the internationally publicized legal proceedings that followed, eight anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

were convicted of conspiracy. The evidence was that one of the defendants may have built the bomb, but none of those on trial had thrown it, and only two of the eight were at the Haymarket at the time. Seven were sentenced to death and one to a term of 15 years in prison. Illinois Governor Richard J. Oglesby commuted two of the sentences to terms of life in prison; another committed suicide in jail before his scheduled execution. The other four were hanged on November 11, 1887. In 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the remaining defendants and criticized the trial.

The Haymarket Affair is generally considered significant as the origin of International Workers' Day held on May 1, and it was also the climax of the social unrest among the working class in America known as the Great Upheaval

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians (french: Le Grand Dérangement or ), was the forced removal, by the British, of the Acadian pe ...

. According to labor historian William J. Adelman:

The site of the incident was designated a Chicago landmark in 1992, and a sculpture was dedicated there in 2004. In addition, the ''Haymarket Martyrs' Monument

The ''Haymarket Martyrs' Monument'' is a funeral monument and sculpture located at Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Dedicated in 1893, it commemorates the defendants involved in labor unrest who were blamed, con ...

'' was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1997 at the defendants' burial site in Forest Park

A forest park is a park whose main theme is its forest of trees. Forest parks are found both in the mountains and in the urban environment.

Examples Chile

* Forest Park, Santiago

China

*Gongqing Forest Park, Shanghai

* Mufushan National Fores ...

.

Background

Following the Civil War, particularly following theLong Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

, there was a rapid expansion of industrial production in the United States. Chicago was a major industrial center and tens of thousands of German and Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

n immigrants were employed at about $1.50 a day. American workers worked on average slightly over 60 hours, during a six-day work week. The city became a center for many attempts to organize labor's demands for better working conditions. Employers responded with anti-union measures, such as firing and blacklisting union members, locking out workers, recruiting strikebreakers; employing spies, thugs, and private security forces and exacerbating ethnic tensions in order to divide the workers. Business interests were supported by mainstream newspapers, and were opposed by the labor and immigrant press.

During the economic slowdown between 1882 and 1886, socialist and anarchist organizations were active. Membership of the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

, which rejected socialism and radicalism, but supported the 8-hour work day, grew from 70,000 in 1884 to over 700,000 by 1886. In Chicago, the anarchist movement of several thousand, mostly immigrant, workers centered about the German-language newspaper ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'' ("Workers' Newspaper"), edited by August Spies. Other anarchists operated a militant revolutionary force with an armed section that was equipped with explosives. Its revolutionary strategy centered around the belief that successful operations against the police and the seizure of major industrial centers would result in massive public support by workers, start a revolution, destroy capitalism, and establish a socialist economy.Henry David, ''The History of the Haymarket Affair'' (1936), introductory chapters, pages 21 to 138

May Day parade and strikes

In October 1884, a convention held by theFederation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada (FOTLU) was a federation of labor unions created on November 15, 1881, at Turner Hall in Pittsburgh. It changed its name to the American Federation of Labor (AF ...

unanimously set May 1, 1886, as the date by which the eight-hour work day would become standard. As the chosen date approached, U.S. labor unions prepared for a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

in support of the eight-hour day.

On Saturday, May 1, thousands of workers who went on strike and attended rallies that were held throughout the United States sang from the anthem, ''Eight Hour.'' The chorus of the song reflected the ideology of the Great Upheaval, "Eight Hours for work. Eight hours for rest. Eight hours for what we will." Estimates of the number of striking workers across the U.S. range from 300,000 to half a million. In New York City, the number of demonstrators was estimated at 10,000. and in Detroit at 11,000.Foner, ''May Day'', p. 28. In Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

, some 10,000 workers turned out. In Chicago, the movement's center, an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 workers had gone on strikeAvrich, ''The Haymarket Tragedy'', p. 186. and there were perhaps twice as many people out on the streets participating in various demonstrations and marches,David, ''The History of the Haymarket Affair'', pp. 177, 188. as, for example, a march by 10,000 men employed in the Chicago lumber yards.Foner, ''May Day'', p. 27. Though participants in these events added up to 80,000, it is disputed whether there was a march of that number down Michigan Avenue led by anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 – November 11, 1887) was a pioneering American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist. As a teenager, he served in the military force of the Confederate States of Americ ...

, founder of the International Working People's Association

The International Working People's Association (IWPA), sometimes known as the "Black International," was an international anarchist political organization established in 1881 at a convention held in London, England. In America the group is best r ...

WPA

WPA may refer to:

Computing

*Wi-Fi Protected Access, a wireless encryption standard

*Windows Product Activation, in Microsoft software licensing

* Wireless Public Alerting (Alert Ready), emergency alerts over LTE in Canada

* Windows Performance An ...

his wife and fellow organizer Lucy

Lucy is an English feminine given name derived from the Latin masculine given name Lucius with the meaning ''as of light'' (''born at dawn or daylight'', maybe also ''shiny'', or ''of light complexion''). Alternative spellings are Luci, Luce, Lu ...

, and their children.

Speaking to a rally outside the plant on May 3, August Spies advised the striking workers to "hold together, to stand by their union, or they would not succeed". Well-planned and coordinated, the general strike to this point had remained largely nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. When the end-of-the-workday bell sounded, however, a group of workers surged to the gates to confront the strikebreakers. Despite calls for calm by Spies, the police fired on the crowd. Two McCormick workers were killed (although some newspaper accounts said there were six fatalities). Spies would later testify, "I was very indignant. I knew from experience of the past that this butchering of people was done for the express purpose of defeating the eight-hour movement."Green, ''Death in the Haymarket'', pp. 162–173.

Outraged by this act of police violence

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, but is not limited to, ...

, local anarchists quickly printed and distributed fliers calling for a rally the following day at Haymarket Square (also called the Haymarket), which was then a bustling commercial center near the corner of Randolph Street and Desplaines Street. Printed in German and English, the fliers stated that the police had murdered the strikers on behalf of business interests and urged workers to seek justice. The first batch of fliers contain the words ''Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force!'' When Spies saw the line, he said he would not speak at the rally unless the words were removed from the flier. All but a few hundred of the fliers were destroyed, and new fliers were printed without the offending words. More than 20,000 copies of the revised flier were distributed.

Rally at Haymarket Square

The rally began peacefully under a light rain on the evening of May 4. August Spies,

The rally began peacefully under a light rain on the evening of May 4. August Spies, Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 – November 11, 1887) was a pioneering American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist. As a teenager, he served in the military force of the Confederate States of Americ ...

, and the Rev. Samuel Fielden spoke to a crowd estimated variously between 600 and 3,000 while standing in an open wagon adjacent to the square on Des Plaines Street. A large number of on-duty police officers watched from nearby.

Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was a historian of the 19th and early 20th century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his entire career, from 19 ...

, a historian specializing in the study of anarchism, quotes Spies as saying:

There seems to prevail the opinion in some quarters that this meeting has been called for the purpose of inaugurating a riot, hence these warlike preparations on the part of so-called 'law and order.' However, let me tell you at the beginning that this meeting has not been called for any such purpose. The object of this meeting is to explain the general situation of the eight-hour movement and to throw light upon various incidents in connection with it.Following Spies' speech, the crowd was addressed by Parsons, the Alabama-born editor of the radical English-language weekly ''

The Alarm

The Alarm are a Welsh rock band that formed in Rhyl, Wales, in 1981. Initially formed as a punk band, the Toilets, in 1977, under lead vocalist Mike Peters, the band soon embraced arena rock and included marked influences from Welsh languag ...

.''Nelson, ''Beyond the Martyrs'', p. 188. The crowd was so calm that Mayor Carter Harrison Sr., who had stopped by to watch, walked home early. Parsons spoke for almost an hour before standing down in favor of the last speaker of the evening, the English-born socialist, anarchist, and labor activist Methodist pastor, Rev. Samuel Fielden, who delivered a brief ten-minute address. Many of the crowd had already left as the weather was deteriorating.

A ''New York Times'' article, with the dateline May 4, and headlined "Rioting and Bloodshed in the Streets of Chicago ... Twelve Policemen Dead or Dying", reported that Fielden spoke for 20 minutes, alleging that his words grew "wilder and more violent as he proceeded". Another ''New York Times'' article, headlined "Anarchy's Red Hand" and dated May 6, opens with: "The villainous teachings of the Anarchists bore bloody fruit in Chicago tonight and before daylight at least a dozen stalwart men will have laid down their lives as a tribute to the doctrine of Herr Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed". His g ...

." It referred to the strikers as a "mob" and used quotation marks around the term "workingmen".

Bombing and gunfire

At about 10:30 pm, just as Fielden was finishing his speech, police arrived en masse, marching in formation towards the speakers' wagon, and ordered the rally to disperse. Fielden insisted that the meeting was peaceful. Police Inspector John Bonfield proclaimed:

At about 10:30 pm, just as Fielden was finishing his speech, police arrived en masse, marching in formation towards the speakers' wagon, and ordered the rally to disperse. Fielden insisted that the meeting was peaceful. Police Inspector John Bonfield proclaimed:

I command you ddressing the speakerin the name of the law to desist and you ddressing the crowdto disperse.A home-made bomb with a brittle metal casing filled with dynamite and ignited by a fuse was thrown into the path of the advancing police. Its fuse briefly sputtered, and then the bomb exploded, killing policeman Mathias J. Degan, who sustained shell wounds in the abdomen and legs by flying metal fragments, and severely wounding many of the other policemen. This is the same article datelined May 4, reproduced elsewhere. Witnesses maintained that immediately after the bomb blast there was an exchange of gunshots between police and demonstrators.Schaack, ''Anarchy and Anarchists'', pp. 146–148. It is unclear who fired first. Historian

Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was a historian of the 19th and early 20th century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his entire career, from 19 ...

maintains that "nearly all sources agree that it was the police who opened fire", reloaded and then fired again, killing at least four and wounding as many as 70 people. In less than five minutes the square was empty except for the casualties. According to the May 4 New York Times, demonstrators began firing at the police, who then returned fire. In his report on the incident, Inspector Bonfield wrote that he "gave the order to cease firing, fearing that some of our men, in the darkness might fire into each other". An anonymous police official told the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

'', "A very large number of the police were wounded by each other's revolvers. ... It was every man for himself, and while some got two or three squares away, the rest emptied their revolvers, mainly into each other."

In all, seven policemen and at least four workers were killed. Avrich maintains that most of the police deaths were from police gunfire. Historian Timothy Messer-Kruse

Timothy F. "Tim" Messer-Kruse (born ) is an American historian who specializes in American labor history. His research into the 1886 Haymarket affair led him to reappraise the conventional narrative about the evidence presented against those bro ...

argues that, although it's impossible to rule out lethal friendly fire, several policemen were probably shot by armed protesters. Another policeman died two years after the incident from complications related to injuries received on that day. It remains the single most deadly incident of officers being killed in the line of duty in the history of the Chicago Police Department. About 60 policemen were wounded in the incident. They were carried, along with some other wounded people, into a nearby police station. Police captain Michael Schaack later wrote that the number of wounded workers was "largely in excess of that on the side of the police". The ''Chicago Herald'' described a scene of "wild carnage" and estimated at least fifty dead or wounded civilians lay in the streets. It is unclear how many civilians were wounded since many were afraid to seek medical attention, fearing arrest. They found aid where they could.Schaack, Michael J. (1889), ''Anarchy and Anarchists'', pp. 149–155.

Aftermath and red scare

A harsh anti-union clampdown followed the Haymarket incident and the Great Upheaval subsided. Employers regained control of their workers and traditional workdays were restored to ten or more hours a day. There was a massive outpouring of community and business support for the police and many thousands of dollars were donated to funds for their medical care and to assist their efforts. The entire labor and immigrant community, particularly Germans and Bohemians, came under suspicion. Police raids were carried out on homes and offices of suspected anarchists. Dozens of suspects, many only remotely related to the Haymarket Affair, were arrested. Casting legal requirements such as search warrants aside, Chicago police squads subjected the labor activists of Chicago to an eight-week shakedown, ransacking their meeting halls and places of business. The emphasis was on the speakers at the Haymarket rally and the newspaper ''Arbeiter-Zeitung''. A small group of anarchists were discovered to have been engaged in making bombs on the same day as the incident, including round ones like the one used in Haymarket Square.Avrich (1984), pp. 221–32.

Newspaper reports declared that anarchist agitators were to blame for the "riot", a view adopted by an alarmed public. As time passed, press reports and illustrations of the incident became more elaborate. Coverage was national, then international. Among property owners, the press, and other elements of society, a consensus developed that suppression of anarchist agitation was necessary while for their part, union organizations such as The Knights of Labor and craft unions were quick to disassociate themselves from the anarchist movement and to repudiate violent tactics as self-defeating.David, ''The History of the Haymarket Affair'' (1936), pages 178–189 Many workers, on the other hand, believed that men of the

A harsh anti-union clampdown followed the Haymarket incident and the Great Upheaval subsided. Employers regained control of their workers and traditional workdays were restored to ten or more hours a day. There was a massive outpouring of community and business support for the police and many thousands of dollars were donated to funds for their medical care and to assist their efforts. The entire labor and immigrant community, particularly Germans and Bohemians, came under suspicion. Police raids were carried out on homes and offices of suspected anarchists. Dozens of suspects, many only remotely related to the Haymarket Affair, were arrested. Casting legal requirements such as search warrants aside, Chicago police squads subjected the labor activists of Chicago to an eight-week shakedown, ransacking their meeting halls and places of business. The emphasis was on the speakers at the Haymarket rally and the newspaper ''Arbeiter-Zeitung''. A small group of anarchists were discovered to have been engaged in making bombs on the same day as the incident, including round ones like the one used in Haymarket Square.Avrich (1984), pp. 221–32.

Newspaper reports declared that anarchist agitators were to blame for the "riot", a view adopted by an alarmed public. As time passed, press reports and illustrations of the incident became more elaborate. Coverage was national, then international. Among property owners, the press, and other elements of society, a consensus developed that suppression of anarchist agitation was necessary while for their part, union organizations such as The Knights of Labor and craft unions were quick to disassociate themselves from the anarchist movement and to repudiate violent tactics as self-defeating.David, ''The History of the Haymarket Affair'' (1936), pages 178–189 Many workers, on the other hand, believed that men of the Pinkerton agency

Pinkerton is a private security guard and detective agency established around 1850 in the United States by Scottish-born cooper Allan Pinkerton and Chicago attorney Edward Rucker as the North-Western Police Agency, which later became Pinkerton ...

were responsible because of the agency's tactic of secretly infiltrating labor groups and its sometimes violent methods of strike breaking.

Legal proceedings

Investigation

The police assumed that an anarchist had thrown the bomb as part of a planned conspiracy; their problem was how to prove it. On the morning of May 5, they raided the offices of the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'', arresting its editor August Spies, and his brother (who was not charged). Also arrested were editorial assistant Michael Schwab and Adolph Fischer, a typesetter. A search of the premises resulted in the discovery of the "Revenge Poster" and other evidence considered incriminating by the prosecution.Schaack

The police assumed that an anarchist had thrown the bomb as part of a planned conspiracy; their problem was how to prove it. On the morning of May 5, they raided the offices of the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'', arresting its editor August Spies, and his brother (who was not charged). Also arrested were editorial assistant Michael Schwab and Adolph Fischer, a typesetter. A search of the premises resulted in the discovery of the "Revenge Poster" and other evidence considered incriminating by the prosecution.Schaack"Core of the Conspiracy"

''Anarchy and Anarchists'', pp. 156–182. On May 7, police searched the premises of

Louis Lingg Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis (d ...

where they found a number of bombs and bomb-making materials.Schaack"My Connection with the Anarchist Cases"

''Anarchy and Anarchists'', pp, 183–205. Lingg's landlord William Seliger was also arrested but cooperated with police and identified Lingg as a bomb maker and was not charged.Messer-Kruse, Timothy (2011), page 21 An associate of Spies, Balthazar Rau, suspected as the bomber, was traced to Omaha and brought back to Chicago. After interrogation, Rau offered to cooperate with police. He alleged that the defendants had experimented with dynamite bombs and accused them of having published what he said was a code word, "Ruhe" ("peace"), in the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'' as a call to arms at Haymarket Square.

Defendants

Rudolf Schnaubelt, the police's lead suspect as the bomb thrower, was arrested twice early on and released. By May 14, when it became apparent he had played a significant role in the event, he had fled the country.Messer-Kruse (2011), pp. 18–21. William Seliger, who had turned state's evidence and testified for the prosecution, was not charged. On June 4, 1886, eight other suspects, however, were indicted by the grand jury and stood trial for being accessories to the murder of Degan. Of these, only two had been present when the bomb exploded. Spies and Fielden had spoken at the peaceful rally and were stepping down from the speaker's wagon in compliance with police orders to disperse just before the bomb went off. Two others had been present at the beginning of the rally but had left and were at Zepf's Hall, an anarchist rendezvous, at the time of the explosion. They were: ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'' typesetter Adolph Fischer and the well-known activistAlbert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 – November 11, 1887) was a pioneering American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist. As a teenager, he served in the military force of the Confederate States of Americ ...

, who had spoken for an hour at the Haymarket rally before going to Zepf's. Parsons, who believed that the evidence against them all was weak, subsequently voluntarily turned himself in, in solidarity with the accused. A third man, Spies's assistant editor Michael Schwab

Michael Schwab (August 9, 1853 – June 29, 1898) was a German-American labor organizer and one of the defendants in the Haymarket Square incident.

Biography Early years

Michael Schwab was born in Bad Kissingen, Franconia in Germany in 1853. H ...

(who was the brother-in-law of Schnaubelt) was arrested as he had been speaking at another rally at the time of the bombing; he was also later pardoned. Not directly tied to the Haymarket rally, but arrested for their militant radicalism were George Engel

George Engel (April 15, 1836November 11, 1887) was a labor union activist executed after the Haymarket riot, along with Albert Parsons, August Spies, and Adolph Fischer.

Early life

George Engel was born to an impoverished family with three ot ...

(who was at home playing cards on that day), and Louis Lingg Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis (d ...

, the hot-headed bomb maker denounced by his associate, Seliger. Another defendant who had not been present that day was Oscar Neebe

Oscar William Neebe I (July 12, 1850 – April 22, 1916) was an anarchist, labor activist and one of the defendants in the Haymarket bombing trial, and one of the eight activist remembered on May 1, International Workers' Day.

Early life

He ...

, an American-born citizen of German descent who was associated with the ''Arbeiter-Zeitung'' and had attempted to revive it in the aftermath of the Haymarket riot.

Of the eight defendants, five – Spies, Fischer, Engel, Lingg and Schwab – were German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

-born immigrants; a sixth, Neebe, was a U.S.-born citizen of German descent. The remaining two, Parsons and Fielden, born in the U.S. and England, respectively, were of British heritage.

Trial

The trial, ''Illinois vs. August Spies et al.'', began on June 21, 1886, and went on until August 11. The trial was conducted in an atmosphere of extreme prejudice by both public and media toward the defendants.Avrich, ''The Haymarket Tragedy'' (1984), pp. 260–262 It was presided over by Judge

The trial, ''Illinois vs. August Spies et al.'', began on June 21, 1886, and went on until August 11. The trial was conducted in an atmosphere of extreme prejudice by both public and media toward the defendants.Avrich, ''The Haymarket Tragedy'' (1984), pp. 260–262 It was presided over by Judge Joseph Gary

Joseph Easton Gary (July 9, 1821 – October 31, 1906) was judge who presided over the trial of eight anarchists tried for their alleged role in the Haymarket Riot. Born in Potsdam, New York, USA, he worked as a carpenter, then moved to St. Louis ...

. Judge Gary displayed open hostility to the defendants, consistently ruled for the prosecution, and failed to maintain decorum. A motion to try the defendants separately was denied.Avrich, ''The Haymarket Tragedy'' (1984), pp. 262–267 The defense counsel included Sigmund Zeisler and William Perkins Black. Selection of a jury was extraordinarily difficult, lasting three weeks, and nearly one thousand people called. All union members and anyone who expressed sympathy toward socialism were dismissed. In the end a jury of 12 was seated, most of whom confessed prejudice against the defendants. Despite their professions of prejudice Judge Gary seated those who declared that despite their prejudices they would acquit if the evidence supported it, refusing to dismiss for prejudice. Eventually the peremptory challenges of the defense were exhausted. Frustrated by the hundreds of jurors who were being dismissed, a bailiff was appointed who selected jurors rather than calling them at random. The bailiff proved prejudiced himself and selected jurors who seemed likely to convict based on their social position and attitudes toward the defendants. The prosecution, led by Julius Grinnell, argued that since the defendants had not actively discouraged the person who had thrown the bomb, they were therefore equally responsible as conspirators. The jury heard the testimony of 118 people, including 54 members of the Chicago Police Department and the defendants Fielden, Schwab, Spies and Parsons. Albert Parsons' brother claimed there was evidence linking the Pinkertons

Pinkerton is a private security guard and detective agency established around 1850 in the United States by Scottish-born cooper Allan Pinkerton and Chicago attorney Edward Rucker as the North-Western Police Agency, which later became Pinker ...

to the bomb. This reflected a widespread belief among the strikers.

Police investigators under Captain Michael Schaack had a lead fragment removed from a policeman's wounds chemically analyzed. They reported that the lead used in the casing matched the casings of bombs found in Lingg's home. A metal nut and fragments of the casing taken from the wound also roughly matched bombs made by Lingg. Schaack concluded, on the basis of interviews, that the anarchists had been experimenting for years with dynamite and other explosives, refining the design of their bombs before coming up with the effective one used at the Haymarket.

At the last minute, when it was discovered that instructions for manslaughter had not been included in the submitted instructions, the jury was called back, and the instructions were given.

Verdict and contemporary reactions

The jury returned guilty verdicts for all eight defendants. Before being sentenced, Neebe told the court that Schaack's officers were among the city's worst gangs, ransacking houses and stealing money and watches. Schaack laughed and Neebe retorted, "You need not laugh about it, Captain Schaack. You are one of them. You are an anarchist, as you understand it. You are all anarchists, in this sense of the word, I must say." Judge Gary sentenced seven of the defendants to death by hanging and Neebe to 15 years in prison. The sentencing provoked outrage from labor and workers' movements and their supporters, resulting in protests around the world, and elevating the defendants to the status of martyrs, especially abroad. Portrayals of the anarchists as bloodthirsty foreign fanatics in the press along with the 1889 publication of Captain Schaack's sensational account, ''Anarchy and Anarchism,'' on the other hand, inspired widespread public fear and revulsion against the strikers and general anti-immigrant feeling, polarizing public opinion. In an article datelined May 4, entitled "Anarchy's Red Hand", ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' had described the incident as the "bloody fruit" of "the villainous teachings of the Anarchists". The ''Chicago Times'' described the defendants as "arch counselors of riot, pillage, incendiarism and murder"; other reporters described them as "bloody brutes", "red ruffians", "dynamarchists", "bloody monsters", "cowards", "cutthroats", "thieves", "assassins", and "fiends". The journalist George Frederic Parsons wrote a piece for ''The Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'' in which he identified the fears of middle-class Americans concerning labor radicalism, and asserted that the workers had only themselves to blame for their troubles. Edward Aveling

Edward Bibbins Aveling (29 November 1849 – 2 August 1898) was an English comparative anatomist and popular spokesman for Darwinian evolution, atheism and socialism. He was also a playwright and actor.

Aveling was the author of numer ...

remarked, "If these men are ultimately hanged, it will be the ''Chicago Tribune'' that has done it." Schaack, who had led the investigation, was dismissed from the police force for allegedly having fabricated evidence in the case but was reinstated in 1892.

Appeals

The case was appealed in 1887 to the Supreme Court of Illinois, then to theUnited States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

where the defendants were represented by John Randolph Tucker, Roger Atkinson Pryor

Roger Atkinson Pryor (July 19, 1828 – March 14, 1919) was a Virginian newspaper editor and politician who became known for his fiery oratory in favor of secession; he was elected both to national and Confederate office, and served as a gen ...

, General Benjamin F. Butler and William P. Black. The petition for ''certiorari

In law, ''certiorari'' is a court process to seek judicial review of a decision of a lower court or government agency. ''Certiorari'' comes from the name of an English prerogative writ, issued by a superior court to direct that the record of ...

'' was denied.

Commutations and suicide

After the appeals had been exhausted, Illinois GovernorRichard James Oglesby

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

commuted Fielden's and Schwab's sentences to life in prison on November 10, 1887. On the eve of his scheduled execution, Lingg committed suicide in his cell with a smuggled blasting cap

A detonator, frequently a blasting cap, is a device used to trigger an explosive device. Detonators can be chemically, mechanically, or electrically initiated, the last two being the most common.

The commercial use of explosives uses electri ...

which he reportedly held in his mouth like a cigar (the blast blew off half his face and he survived in agony for six hours).

Executions

The next day (November 11, 1887) four defendants—Engel, Fischer, Parsons, and Spies—were taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods. They sang the ''

The next day (November 11, 1887) four defendants—Engel, Fischer, Parsons, and Spies—were taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods. They sang the ''Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" is the national anthem of France. The song was written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in Strasbourg after the declaration of war by France against Austria, and was originally titled "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du R ...

'', then the anthem of the international revolutionary movement. Family members including Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons (born Lucia Carter; 1851 – March 7, 1942) was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marriage ...

, who attempted to see them for the last time, were arrested and searched for bombs (none was found). According to witnesses, in the moments before the men were hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

, Spies shouted, "The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today."Avrich, ''The Haymarket Tragedy'', p. 393. In their last words, Engel and Fischer called out, "Hurrah for anarchism!" Parsons then requested to speak, but he was cut off when the signal was given to open the trap door. Witnesses reported that the condemned men did not die immediately when they dropped, but strangled to death slowly, a sight which left the spectators visibly shaken.

Identity of the bomber

Notwithstanding the convictions for conspiracy, no actual bomber was ever brought to trial, "and no lawyerly explanation could ever make a conspiracy trial without the main perpetrator seem completely legitimate." Historians such asJames Joll

James Bysse Joll FBA (21 June 1918 – 12 July 1994) was a British historian and university lecturer whose works included ''The Origins of the First World War'' and ''Europe Since 1870''. He also wrote on the history of anarchism and socialism ...

and Timothy Messer-Kruse

Timothy F. "Tim" Messer-Kruse (born ) is an American historian who specializes in American labor history. His research into the 1886 Haymarket affair led him to reappraise the conventional narrative about the evidence presented against those bro ...

say the evidence points to Rudolph Schnaubelt, brother-in-law of Schwab, as the likely perpetrator.John J. Miller"What Happened at Haymarket? A historian challenges a labor-history fable"

''National Review'', February 11, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

Documents

An extensive collection of documents relating to the Haymarket Affair and the legal proceedings related to it, The Haymarket Affair Digital Collection, has been created by theChicago Historical Society

Chicago History Museum is the museum of the Chicago Historical Society (CHS). The CHS was founded in 1856 to study and interpret Chicago's history. The museum has been located in Lincoln Park since the 1930s at 1601 North Clark Street at the int ...

.

Pardons and historical characterization

miscarriage of justice

A miscarriage of justice occurs when a grossly unfair outcome occurs in a criminal or civil proceeding, such as the conviction and punishment of a person for a crime they did not commit. Miscarriages are also known as wrongful convictions. Inno ...

. Prominent people such as novelist William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells (; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American realist novelist, literary critic, and playwright, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ...

, celebrated attorney Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

, poet and playwright Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, playwright George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, and poet William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

strongly condemned it. On June 26, 1893, Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld, the progressive governor of Illinois, himself a German immigrant, signed pardons for Fielden, Neebe, and Schwab, calling them victims of "hysteria, packed juries, and a biased judge" and noting that the state "has never discovered who it was that threw the bomb which killed the policeman, and the evidence does not show any connection whatsoever between the defendants and the man who threw it". Altgeld also faulted the city of Chicago for failing to hold Pinkerton guards responsible for repeated use of lethal violence against striking workers. Altgeld's actions concerning labor were used to defeat his reelection.

Soon after the trial, anarchist Dyer Lum

Dyer Daniel Lum (February 15, 1839 – April 6, 1893) was an American anarchist, labor activist and poet. A leading syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s, Lum is best remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarch ...

wrote a history of the trial critical of the prosecution. In 1888, George McLean, and in 1889, police captain Michael Shack, wrote accounts from the opposite perspective. Awaiting sentencing, each of the defendants wrote their own autobiographies (edited and published by Philip Foner

Philip Sheldon Foner (December 14, 1910 – December 13, 1994) was an American labor historian and teacher. Foner was a prolific author and editor of more than 100 books. He is considered a pioneer in his extensive works on the role of radical ...

in 1969), and later activist Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons (born Lucia Carter; 1851 – March 7, 1942) was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marriage ...

published a biography of her condemned husband Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 – November 11, 1887) was a pioneering American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist. As a teenager, he served in the military force of the Confederate States of Americ ...

. Fifty years after the event, Henry David wrote a history, which preceded another scholarly treatment by Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was a historian of the 19th and early 20th century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his entire career, from 19 ...

in 1984, and a "social history" of the era by Bruce C. Nelson in 1988. In 2006, labor historian James Green wrote a popular history.

Christopher Thale writes in the '' Encyclopedia of Chicago'' that lacking credible evidence regarding the bombing, "...the prosecution focused on the writings and speeches of the defendants." He further notes that the conspiracy charge was legally unprecedented, the Judge was "partisan," and all the jurors admitted prejudice against the defendants. Historian Carl Smith writes, "The visceral feelings of fear and anger surrounding the trial ruled out anything but the pretense of justice right from the outset." Smith notes that scholars have long considered the trial a "notorious" "miscarriage of justice". In a review somewhat more critical of the defendants, historian Jon Teaford concludes that " e tragedy of Haymarket is the American justice system did not protect the damn fools who most needed that protection... It is the damn fools who talk too much and too wildly who are most in need of protection from the state." Historian Timothy Messer-Kruse

Timothy F. "Tim" Messer-Kruse (born ) is an American historian who specializes in American labor history. His research into the 1886 Haymarket affair led him to reappraise the conventional narrative about the evidence presented against those bro ...

revisited the digitized trial transcript and argued that the proceedings were fair for their time, a challenge to the historical consensus that the trial was a travesty.

Effects on the labor movement and May Day

Historian Nathan Fine points out that trade-union activities continued to show signs of growth and vitality, culminating later in 1886 with the establishment of the Labor Party of Chicago.Nathan Fine, ''Labor and Farmer Parties in the United States, 1828–1928.'' New York: Rand School of Social Science, 1928; pg. 53. Fine observes:e fact is that despite police repression, newspaper incitement to hysteria, and organization of the possessing classes, which followed the throwing of the bomb on May 4, the Chicago wage earners only united their forces and stiffened their resistance. The conservative and radical central bodies – there were two each of the trade unions and two also of the Knights of Labor — the socialists and the anarchists, theOn the first anniversary of the event, May 4, 1887, the ''single tax A single tax is a system of taxation based mainly or exclusively on one tax, typically chosen for its special properties, often being a tax on land value. The idea of a single tax on land values was proposed independently by John Locke and Bar ...ers and the reformers, the native born...and the foreign born Germans, Bohemians, and Scandinavians, all got together for the first time on the political field in the summer following the Haymarket Affair.... e Knights of Labor doubled its membership, reaching 40,000 in the fall of 1886. On Labor Day the number of Chicago workers in parade led the country.

New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' published an interview with Senator Leland Stanford, in which he addressed the consensus that "the conflict between capital and labor is intensifying" and articulated the vision advocated by the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

for an industrial system of worker-owned co-operatives, another among the strategies pursued to advance the conditions of laborers. The interview was republished as a pamphlet to include the bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

Stanford introduced in the Senate to foster co-operatives.

Popular pressure continued for the establishment of the 8-hour day. At the convention of the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

(AFL) in 1888, the union decided to campaign for the shorter workday again. May 1, 1890, was agreed upon as the date on which workers would strike for an eight-hour work day.

In 1889, AFL president

In 1889, AFL president Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

wrote to the first congress of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

, which was meeting in Paris. He informed the world's socialists of the AFL's plans and proposed an international fight for a universal eight-hour work day. In response to Gompers's letter, the Second International adopted a resolution calling for "a great international demonstration" on a single date so workers everywhere could demand the eight-hour work day. In light of the Americans' plan, the International adopted May 1, 1890, as the date for this demonstration.Foner, ''May Day'', p. 42.

A secondary purpose behind the adoption of the resolution by the Second International was to honor the memory of the Haymarket martyrs and other workers who had been killed in association with the strikes on May 1, 1886. Historian Philip Foner

Philip Sheldon Foner (December 14, 1910 – December 13, 1994) was an American labor historian and teacher. Foner was a prolific author and editor of more than 100 books. He is considered a pioneer in his extensive works on the role of radical ...

writes " ere is little doubt that everyone associated with the resolution passed by the Paris Congress knew of the May 1 demonstrations and strikes for the eight-hour day in 1886 in the United States ... and the events associated with the Haymarket tragedy."

The first International Workers Day

International Workers' Day, also known as Labour Day in some countries and often referred to as May Day, is a celebration of labourers and the working classes that is promoted by the international labour movement and occurs every year on 1 May, ...

was a spectacular success. The front page of the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

'' on May 2, 1890, was devoted to coverage of the event. Two of its headlines were "Parade of Jubilant Workingmen in All the Trade Centers of the Civilized World" and "Everywhere the Workmen Join in Demands for a Normal Day". ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' of London listed two dozen European cities in which demonstrations had taken place, noting there had been rallies in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

and Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

. Commemoration of May Day became an annual event the following year.

The association of May Day with the Haymarket martyrs has remained strong in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

. Mary Harris "Mother" Jones was in Mexico on May 1, 1921, and wrote of the "day of 'fiestas'" that marked "the killing of the workers in Chicago for demanding the eight-hour day". In 1929, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' referred to the May Day parade in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

as "the annual demonstration glorifying the memory of those who were killed in Chicago in 1887". ''The New York Times'' described the 1936 demonstration as a commemoration of "the death of the martyrs in Chicago". In 1939, Oscar Neebe's grandson attended the May Day parade in Mexico City and was shown, as his host told him, "how the world shows respect to your grandfather".

The influence of the Haymarket Affair was not limited to the celebration of May Day. Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, the activist and political theorist, was attracted to anarchism after reading about the incident and the executions, which she later described as "the events that had inspired my spiritual birth and growth". She considered the Haymarket martyrs to be "the most decisive influence in my existence". Her associate, Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Be ...

also described the Haymarket anarchists as "a potent and vital inspiration".Avrich, ''The Haymarket Tragedy'', p. 434. Others whose commitment to anarchism, or revolutionary socialism, crystallized as a result of the Haymarket Affair included Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre (November 17, 1866 – June 20, 1912) was an American anarchist known for being a prolific writer and speaker who opposed capitalism, marriage and the state as well as the domination of religion over sexuality and women's li ...

and "Big Bill" Haywood, a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

. Goldman wrote to historian Max Nettlau that the Haymarket Affair had awakened the social consciousness of "hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people".

Suspected bombers

While admitting that none of the defendants was involved in the bombing, the prosecution made the argument that Lingg had built the bomb, and two prosecution witnesses (Harry Gilmer and Malvern Thompson) tried to imply that the bomb thrower was helped by Spies, Fischer and Schwab. The defendants claimed they had no knowledge of the bomber at all. Several activists, including Robert Reitzel, later hinted they knew who the bomber was. Writers and other commentators have speculated about many possible suspects: * Rudolph Schnaubelt (1863–1901) was an activist and the brother-in law of Michael Schwab. He was at the Haymarket when the bomb exploded. General Superintendent of the Chicago Police Department Frederick Ebersold issued a handwritten bulletin for his arrest for murder and inciting a riot on June 14, 1886. Schnaubelt was indicted with the other defendants but fled the city and later the country before he could be brought to trial. He was the detectives' lead suspect, and state witness Gilmer testified he saw Schnaubelt throw the bomb, identifying him from a photograph in court. Schnaubelt later sent two letters from London disclaiming all responsibility, writing, "If I had really thrown this bomb, surely I would have nothing to be ashamed of, but in truth I never once thought of it." He is the most generally accepted and widely known suspect and figured as the bomb thrower in ''The Bomb'',

* Rudolph Schnaubelt (1863–1901) was an activist and the brother-in law of Michael Schwab. He was at the Haymarket when the bomb exploded. General Superintendent of the Chicago Police Department Frederick Ebersold issued a handwritten bulletin for his arrest for murder and inciting a riot on June 14, 1886. Schnaubelt was indicted with the other defendants but fled the city and later the country before he could be brought to trial. He was the detectives' lead suspect, and state witness Gilmer testified he saw Schnaubelt throw the bomb, identifying him from a photograph in court. Schnaubelt later sent two letters from London disclaiming all responsibility, writing, "If I had really thrown this bomb, surely I would have nothing to be ashamed of, but in truth I never once thought of it." He is the most generally accepted and widely known suspect and figured as the bomb thrower in ''The Bomb'', Frank Harris

Frank Harris (14 February 1855 – 26 August 1931) was an Irish-American editor, novelist, short story writer, journalist and publisher, who was friendly with many well-known figures of his day.

Born in Ireland, he emigrated to the United State ...

's 1908 fictionalization of the tragedy. Written from Schnaubelt's point of view, the story opens with him confessing on his deathbed. However, Harris's description was fictional and those who knew Schnaubelt vehemently criticized the book.

* George Schwab was a German shoemaker who died in 1924. German anarchist Carl Nold claimed he learned Schwab was the bomber through correspondence with other activists but no proof ever emerged. Historian Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was a historian of the 19th and early 20th century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his entire career, from 19 ...

also suspected him but noted that while Schwab was in Chicago, he had only arrived days before. This contradicted statements by others that the bomber was a well-known figure in Chicago.

* George Meng (b. around 1840) was a German anarchist and teamster who owned a small farm outside of Chicago where he had settled in 1883 after emigrating from Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. Like Parsons and Spies, he was a delegate at the Pittsburgh Congress and a member of the IWPA. Meng's granddaughter, Adah Maurer, wrote Paul Avrich a letter in which she said that her mother, who was 15 at the time of the bombing, told her that her father was the bomber. Meng died sometime before 1907 in a saloon fire. Based on his correspondence with Maurer, Avrich concluded that there was a "strong possibility" that the little-known Meng may have been the bomber.

* An agent provocateur

An agent provocateur () is a person who commits, or who acts to entice another person to commit, an illegal or rash act or falsely implicate them in partaking in an illegal act, so as to ruin the reputation of, or entice legal action against, th ...

was suggested by some members of the anarchist movement. Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 – November 11, 1887) was a pioneering American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist. As a teenager, he served in the military force of the Confederate States of Americ ...

believed the bomber was a member of the police or the Pinkertons trying to undermine the labor movement. However, this contradicts the statements of several activists who said the bomber was one of their own. For example, Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons (born Lucia Carter; 1851 – March 7, 1942) was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marriage ...

and Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed". His g ...

rejected this notion. Dyer Lum

Dyer Daniel Lum (February 15, 1839 – April 6, 1893) was an American anarchist, labor activist and poet. A leading syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s, Lum is best remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarch ...

said it was "puerile" to ascribe "the Haymarket bomb to a Pinkerton".

* A disgruntled worker was widely suspected. When Adolph Fischer was asked if he knew who threw the bomb, he answered, "I suppose it was some excited workingman." Oscar Neebe said it was a "crank". Governor Altgeld speculated the bomb thrower might have been a disgruntled worker who was not associated with the defendants or the anarchist movement but had a personal grudge against the police. In his pardoning statement, Altgeld said the record of police brutality toward the workers had invited revenge adding, "Capt. Bonfield is the man who is really responsible for the deaths of the police officers."

* Klemana Schuetz was identified as the bomber by Franz Mayhoff, a New York anarchist and fraudster, who claimed in an affidavit that Schuetz had once admitted throwing the Haymarket bomb. August Wagener, Mayhoff's attorney, sent a telegram from New York to defense attorney Captain William Black the day before the executions claiming knowledge of the bomber's identity. Black tried to delay the execution with this telegram but Governor Oglesby refused. It was later learned that Schuetz was the primary witness against Mayhoff at his trial for insurance fraud, so Mayhoff's affidavit has never been regarded as credible by historians.

* Reinold "Big" Krueger was killed by police either in the melee after the bombing or in a separate disturbance the next day and has been named as a suspect but there is no supporting evidence.

* A mysterious outsider was reported by John Philip Deluse, a saloon keeper in Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

who claimed he encountered a stranger in his saloon the day before the bombing. The man was carrying a satchel and on his way from New York to Chicago. According to Deluse, the stranger was interested in the labor situation in Chicago, repeatedly pointed to his satchel and said, "You will hear of some trouble there very soon." Parsons used Deluse's testimony to suggest the bomb thrower was sent by eastern capitalists. Nothing more was ever learned about Deluse's claim.

Burial and monument

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons were buried at the

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons were buried at the German Waldheim Cemetery

Forest Home Cemetery is at 863 S. DesPlaines Ave, Forest Park, Illinois, adjacent to the Eisenhower Expressway, straddling the Des Plaines River in Cook County, just west of Chicago. The cemetery traces its history to two adjacent cemeteries, G ...